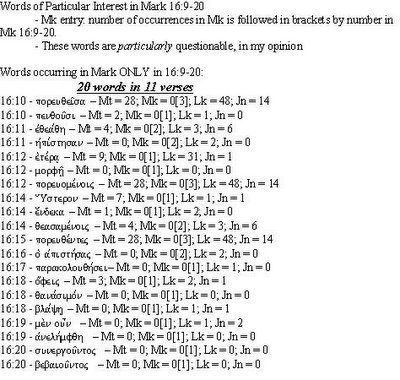

However, other word are highly suspect also.

I have not concluded that the Long Ending (LE) was not inspired based upon my little word counting. This internal data raises "questions," and that's all. The external data is supportive. The content is also suggestive. These three, not one aspect alone, are all suggestive that the LE is not original to Mark. The definition of "questionable" words was "loose" on purpose. Its design, primarily, was to point out words that deserve a closer examination. It does not mean that these words are evidence against Marken authorship. It just means that these are the words that need to be examined in greater detail regarding this subject. That's it. This list of hapax or near hapax's is much more evidential in nature than the "questionable" list.

My conclusion is that the vocab, at the very least, poses a problem for those who want to include that Mark 16:9-20 is original to the Gospel and is part of the canon (a slightly separate issue which needs to be discussed after one concludes on the originality of the passage). If textual criticism were as easy as counting manuscripts then anyone could do it. However, it is more complicated than that. While I don't want to lay some of the foundational principles of textual criticism, I will touch on some.

Some scholars do textual criticism by counting the number of manuscripts that contain a passage and manuscripts that don't. The larger number wins. This method is ludicrous. Since so many of the later copies of the Byzantine text-type can be traced to only a few manuscripts, more does not mean better attested. Geographic distribution is a better gage at authenticity. However, the data here is not convincing either. One could look at a text-critical chart on Mark 16 may lead to the conclusion that the external data at least seems to favor inclusion of the LE. However, note thefollowing: 1) The oldest manuscripts are Aleph and B. So while they only total two, they are dated in the 4th century. 2) The Byzantine text-type is not consistent and many scribes saw the inclusion of the LE but concluded that it was spurious (not original). They did this through the inclusion of a note or sign (e.g., an asterisk). 3) Eusebius and Jerome (5th cent.) say that the LE is in almost no Greek manuscripts that they could find. 4) In the Western text-type, one manuscript did not have the LE, but only a different, shorter ending (itk). So, all three text-types have manuscripts that include and don't include the LE. Why would older NOT be better. What is argument to say that older manuscripts are more likely wrong? Not only are Aleph and B dated to the 4th cent (A, the Byzantine codex, is dated the 5th cent.; the other Byzantine texts are from the 8th to 13th cents.), but many Sinaitic Syriac manuscripts, a hundred or so Armenian texts, two Georgian texts (from the 9th and 10th cent), and Clement of Alexandria, Jerome, and Eusebius, and Origen support exclusion of the LE. Also, Codex Bobiensis (k) omits the LE which is, to quote Metzger, "the most important witness to the Old African Latin" Bible (Metzger, Text ofthe NT, 73).That said, the external evidence, by itself, will not convince. However, the internal evidence, if one's text-critical theory allows, may be convincing.

The internal evidence isn't just vocab, but syntactical phrases that Mark uses only in 16:9-20. Also included is the extremely awkward flow from 16:8 to 16:9. While the subject of verse 8 was the women, in verse 9 it switches to Jesus by the use of a third person singular verb … no explicit subject: "for they were afraid. 9 Nowafter He had risen". In verse 9, Mary Magdalene is introduced as if she had not been the topic of the preceding verses (cf. 16:1). And, what happened to the other women of verses 1-8.Therefore, without a rebuttal to the internal evidence (as Farmer attempted, but honestly utterly failed), it isn't enough tosay "well, that's just the internal (thus subjective) evidence." Demonstrate it's subjectiveness. Demonstrate that the evidence from vocab is not convincing … the translators of the NAS, NIV, RSV,NRSV, ASV, NLT, CEV, etc, all found SOMETHING convincing?! Demonstrate that the syntactical phrases in the LE are not unique. Give evidence that the awkward transition between 16:8 and 16:9 is not awkward. Another basic premise of textual criticism is explaining the spurious reading. If the LE is original, explain why someone would shorten it to verse 8 purposely. Because of the content of part of verse 8 and 18? Why not just take those verses out? Why delete the entire resurrection narrative? How can you account for teaching found in Mk 16:9-20 which is nowhere else in any of the four Gospels: snake handling, drinking poison, speaking in tongues, and vs. 16 which, on the surface at least, appears to say that baptism is necessary for salvation. Most rebuttals that I have seen simply refer to the subjective nature of internal evidence. However, realize this: if you reject these principles of textual criticism, then this has serious repercussions for the Bible you use: the translators of the NIV, NAS, etc, all accept these principles. You are left with the KJV, NKJV (and, at times, the Holman Christian Standard Bible). As far as a Greek text goes, there are only two that I know of that you could get: the Robinson-Pierpoint and the Hodges-Farstad (yes, that is Zane Hodges).

Regarding canonical issues: when do specific pericopae become discussions of canon? In other words, admission into the canon was based upon the book, not a certain version of a book. It was recognized early that Mark had multiple endings being circulated, however, I can't find any discussion over "which Mark" is canonical. This also applies to Septuagintal studies: There were many Septuagint versions circulating, and "competing" versions were considered canonical. I don't think the early church, in their discussions, debated over the canonical status of a pericope in a canonical book. Also, church history should not be decisive, in my opinion. Many, many held to the canonical status of Paul's letter to the Laodiceans until the 11th century (or so). How many Christians have ever read or studied this letter? Many in church history held to the canonical status of the Shepherd of Hermes and the Didache. However, most people I know have no idea about the content of these letters. Anyhow, these are some preliminary questions about the canonical status of the LE. Me? I would say simply that some communities held to its canonicity and others didn't. However, ifyou decide that it is not original, it is hard for me to figure out how it could be canonical. Metzger, by the way, says the LE was not original but IS canonical.

1 comment:

Dave,

Great post. A bit long, but good! Congrats on finishing up your dissertation.

J. B. Hood

Post a Comment